Abstract

The built environment in Pakistan has historically neglected to accommodate people with physical disabilities and continues to do so with no consideration for the severe limitations of such citizens. May they be restaurants, shopping centers, bus-stops, public-lavatories, there is no way for the handicapped to independently access these facilities. To demonstrate this issue in detail, a survey of about 80 restaurants was conducted in Lahore. These eateries are some of the busiest and high grossing restaurants and diners in their areas. The survey entailed evaluating the buildings that these places are housed in and their capacity to facilitate the physically challenged customers. The findings of this report have been documented in detail for policymakers, and designers in particular, in understanding the situation as it is. Accommodating the physically disabled population is a fundamental civic requirement and a human rights concern for any country of the world. In Pakistan it can no longer be overlooked or dismissed.

Key Words

Disability, Accessibility, Inclusivity, Universal Design, Restaurants, Public Spaces, Design for All

Introduction

A society's progress in social welfare can be measured by how well physically and mentally disabled people are integrated into positive interactions. Because disability is viewed as a disruption to the 'natural order of things,' the pursuit for a solution is mandatory.

Ronald Mace, an architect, developed the term "universal design" to define accessibility that extends beyond the limits of barrier-free design (Mace 1985). Mace expressed Universal Design as an approach of designing a building or structure that is both appealing and feasible for all individuals, disabled or not while also eliminating the recognized appearance of many present accessible designs. The objective was to make the environment "functional for all people" and the integration of disability into broader conceptions (Boys J. 2017).

The concept of Universal Design reflected a desire to emphasize the aesthetics and function of access, rather than considering disabilities as an added, supplementary, and unusual issue - that is, as a "special need." (Imrie, R., & Hall, P. 2003). Universal design enhances the possibility of improving the quality of life for a wide range of individuals It also decreases stigma by putting disabled persons on an equal playing field with the able-bodied population.

Numerous advocacy organizations dedicated to enhancing the lifestyle of individuals with disabilities have posited that the exclusion of this demographic from mainstream society is not inherent to their disabilities but is predominantly a consequence of inadequate physical infrastructure. This approach results in the creation of inflexible and stagnant spaces that cater only to a specific user group, erecting barriers for those who deviate from the conventional notion of able bodies. (Reid, R. 2021).

Pakistan's built environment is relatively underdeveloped in terms of facilitating systems for people with impairments. Disability is difficult to identify and evaluate since it is underreported by the community, particularly women (World Bank, 2011). It has been found that society tends to disregard them, considering them incapable of engaging in the community or avoiding them as reminders of their weakness. They do not receive disability-related services in accordance with their needs, and they are severely excluded from everyday life (Afzal, 2020). People with disabilities and their needs are being seen as a human rights concern on a global scale while there is evidence that people with impairments have poorer economic success than those without disabilities.

Millions of individuals in Pakistan suffer from various types of impairments. Nonetheless our societies and government organizations have generally ignored the needs of handicapped individuals, despite the fact that many of them have the potential to become well-integrated and productive members of society (Muhammad Ali, 2022).

People with disabilities (PWDs) face a wide variety of challenges, including cognitive, developmental, mental, physical, and sensory restrictions. According to the UNDP, around 6.2% of Pakistanis have a disability. Other estimates place this part far higher. Human Rights Watch estimates the number of people with disabilities in Pakistan to be between 3.3 and 27 million.

Lack of Provisions Regarding Disability in Pakistan’s Construction Bylaws

Several initiatives were introduced in Pakistan to rehabilitate the disabled in different ways. One aspect was to facilitate their access to public spaces. The laws approved by government organizations such as the Special Citizens Act of 2008 aim directly at making every public space accessible to handicapped citizens including the allotment of seats in public transport and the provision of amenities on pathways for wheelchairs and for blind people. Under this act, it is incumbent upon the government to ensure that the concerned authorities design wheelchair access before the construction of buildings in both the public or private sectors, (Ahmed M., 2011) yet there is a notable absence of implementation of such provisions even in high profile areas such as the DHA (Defense Housing Authority).

The legal framework does not explicitly mandate features such as accessibility measures, open spaces conducive to wheelchair use, or signage designed to enhance inclusivity. This lack of explicit legal provisions contributes to a prevailing gap in the implementation of disabled-friendly construction techniques within the constructed environment. As a result, commercial buildings, including restaurants, often do not reflect the necessary accommodations for individuals with disabilities and thus fails to provide a desired design and, the reason being that Lahore's commercial industry lacks verifiable data and sufficient research committed to addressing this particular issue.

Universal Design Approach

In the disability criteria, there is a common assumption that designers overlook the needs of disabled people by limiting their approach to what is required by abled-bodied people. While considering the design parameters for disability one has to be creative with complex design strategies to be implemented on site. Exploring the disabling effects it can have on disabled people, on our understandings of able and disabled, on the concept of material space and on architecture as a whole (Boys J., 2014).

Universal design requires designers to create

environments and products that cater to people as individuals and increase their sense of self-sufficiency as capable members of society.

From the following studies there has been seven principles of universal design strategies adopted to achieve all aspects of a good design. These standards give a benchmark for measuring objects and environments.

Table 1

Methodology of the Survey

A team survey was conducted in more than 80 restaurants within the two major commercial zones of Lahore, i.e. DHA and Gulberg, to evaluate the facilities that allow accessibility and mobility of physically disabled people in each of these eateries. The required information was gathered by means of a questionnaire.

The scope of this study was qualitative and quantitative survey of the implementation of universal design approach of restaurants in Gulberg and DHA Lahore.

The study examines and identifies the problems of existing restaurants providing access, flexible layout design and other inclusive design considerations and draws recommendations to improve the overall accessibility for disabled users.

Table 2

|

S.No |

Name of Restaurant (Gulberg) |

S.No |

Name of Restaurant (DHA) |

|

1. |

Cinnabon |

47. |

McDonald’s |

|

2. |

Coco Cubano |

48. |

Second cup |

|

3. |

Villa the grand buffet |

49. |

Gloria jean’s coffees |

|

4. |

Lahore chatkhara |

50. |

Dogar restaurant |

|

5. |

Junoon |

51. |

14th street pizza |

|

6. |

Theatre |

52. |

Veera 5 |

|

7. |

Optp |

53. |

Jessie’s burger |

|

8. |

Mocha coffee |

54. |

Gourmet grill |

|

9. |

Bon vivant palais |

55. |

Butt karahi |

|

10. |

The Brasseries |

56. |

Pagla bawarchi |

|

11. |

Nando’s |

57. |

Bundu khan |

|

12. |

Nisa Sultan |

58. |

Daily deli co. |

|

13. |

Ox & grill steakhouse |

59. |

Meet the buns |

|

14. |

The Pantry |

60. |

Jade café and Chinatown |

|

15. |

Howdy |

61. |

London courtyard |

|

16. |

KFC |

62. |

Rina’s kitchenette |

|

17. |

Chaye khana |

63. |

Cosa nostra |

|

18. |

Saku Hana |

64. |

Subway |

|

19. |

QB’z |

65. |

Dip and sip |

|

20. |

Café Beirut |

66. |

Ice food |

|

21. |

Soul kitchen and café |

67. |

Mandarin kitchen |

|

22. |

Amavi |

68. |

Baskin Robbins |

|

23. |

Hardee’s |

69. |

Dunkin donuts |

|

24. |

Gloria Jean’s coffees |

70. |

Coffee planet |

|

25. |

Bar b q tonight |

71. |

Go Sushi |

|

26. |

Nando’s |

72. |

The burning giraffe |

|

27. |

Second cup |

73. |

Juicy chuck |

|

28. |

Bagh |

74. |

Wok and co. |

|

29. |

Salt and pepper village |

75. |

The rice bowl |

|

30. |

Jade café |

76. |

Hardee’s |

|

31. |

Freddy’s café |

77. |

Nando’s |

|

32. |

Baranh |

78. |

Domino’s |

|

33. |

Eggspectation |

79. |

Bob’s |

|

34. |

Rare |

80. |

Papa john’s |

|

35. |

Urban kitchen |

81. |

Pataka boti |

|

36. |

Butler’s chocolate café |

|

|

|

37. |

Tuscany courtyard |

|

|

|

38. |

Forks and knives |

|

|

|

39. |

Fuchsia kitchen |

|

|

|

40. |

PF Chang’s |

|

|

|

41. |

Café Aylanto |

|

|

|

42. |

Yums |

|

|

|

43. |

Sichuan |

|

|

|

44. |

East Chinese |

|

|

|

45. |

Monal |

|

|

|

46. |

Lamour |

|

|

With an absence of a comprehensive toolkit for evaluating universal design and the lack of legislations in Pakistan specific to this context, the study is based on internationally recognized tools such as the Universal Design Principles (UDP) mentioned above and the guidelines for the implementation of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA, 1990). The principles are lofty objectives followed by subsets of principles and design ideas that are relatively generic in nature and cannot be quantified. The problem is to bring forth into design the Seven Principles and match them with the performance criteria, standards, and guidelines that designers and planners are accustomed to (Preiser, W. 2008).

These frameworks provide a set of guiding principles that encompass various aspects of design, including accessibility, flexibility, and simplicity.

Design Attributes for Assessing the Inclusivity

In order to evaluate the performance of the built environment of the restaurants as a universal design approach the assessment tool for this study is divided into eight sections that are selected on the basis of guidelines provided by the seven principles of universal design and the approach of ADA guidelines through a proper literature analysis of the two guidelines. The assessment tool employed in this study featured dichotomous questions, providing two distinct options of "yes" or "no" for each query. The details of each section are provided in the following table.

Table 3

|

S.No |

Design Attributes |

Detailed Parameters |

|

1. |

Entrance and parking |

Access points Accessible

parking Entrance door |

|

2. |

Ramp |

Ramps for entrance |

|

3. |

Tactile |

Material and

finishes Surface

treatments |

|

4. |

Signage |

Signage for ramp, entrance, exit ,

stairs, toilets and parking |

|

5. |

Handrails on entrance |

Height and availability of handrails |

|

6. |

Circulation space for wheelchair |

Wide exterior

and interior space for mobility Vertical

circulation Flexible layout |

|

7. |

Accessible toilets |

Separate

restroom for disabled Accessible

entrance through wheelchair Tactile

flooring Grab bars Height of

fixtures |

|

8. |

Emergency exit |

Separate exit for emergency |

Specific

questions were formulated on the basis of the seven universal design principles

for assessment of the restaurant’s infrastructure (Table 4).

Table 4

Questionnaire for the restaurant’s inclusivity assessment.

Results

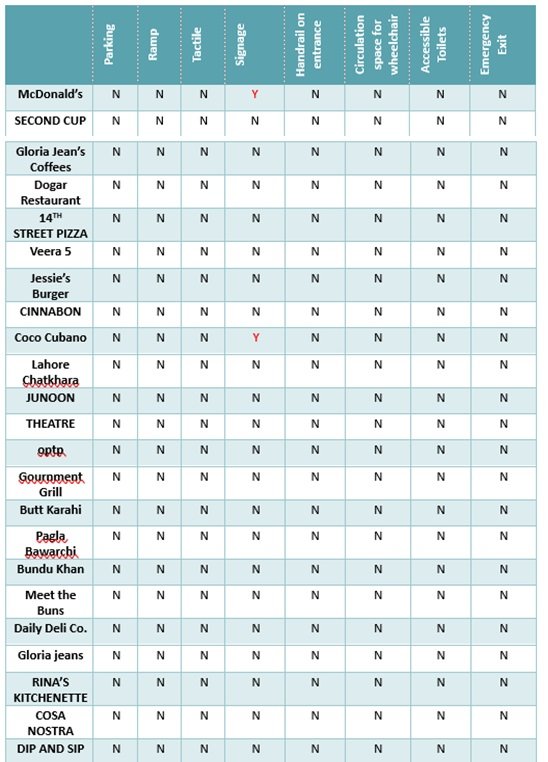

The assessment of restaurants was conducted based on a set of inclusivity design parameters and the questions formulated on the basis of UDP. Regrettably, the majority of the restaurants fell short of meeting the established inclusivity norms. Notably, variations were observed among different locations regarding the presence and absence of specific parameters. This comprehensive evaluation serves as a foundation for identifying specific areas of improvement and tailoring recommendations to enhance the overall inclusivity of restaurants in the studied areas of DHA and Gulberg Lahore (Table 5).

Table 5

Table 6

Table 7

Entrance and Parking

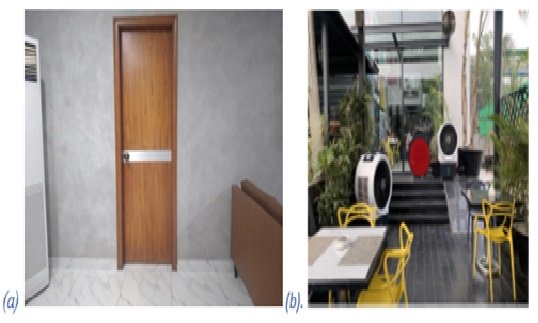

The assessment results revealed that only one out of over 80 restaurants had both an allotted parking space and an approachable entrance for disabled individuals but with no designated signage given shows the lack of proper commitment to an inclusive design approach. The findings underscore the absence of accessible parking spots and no designated accessible route that directly connects to the entrance. Most of the restaurants are at close proximity to the road and hence have a messy and congested entrance where it is difficult for disabled users to approach. Fig 1(a), (b).

Figure 1 (a)(b)

Figure 2

The entrances to almost all the restaurants are inaccessible in terms of a direct route as all have raised floors with steps for entrance. Fig 2(a) Shows the entrance to the restaurant which is five steps above the road level and is completely inaccessible while showing that in Fig 2(b) the parking for the restaurant is on the opposite side of the service lane which makes it practically impossible for disabled users to utilize this space.

Ramps

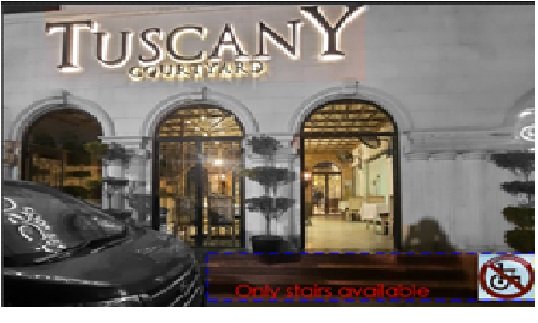

The observation that most restaurants in Pakistan have entrances elevated above road level, primarily accessible via stairs, underscores a widespread lack of inclusive design practices within the country.

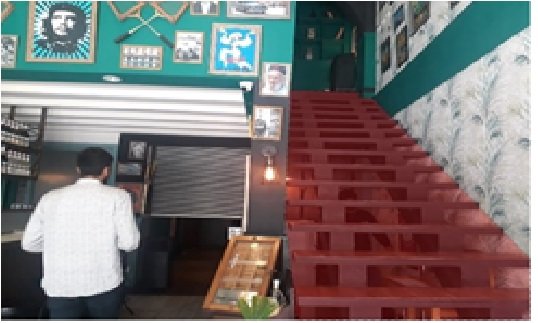

Out of over 80 assessed restaurants, only thirteen had ramps while majority had no ramps at all reflecting an ample deficiency in design. There are narrow entrances, no parking spaces provided, and the entrance doors in most of these

restaurants are not according to the standards, leading towards the absence of an inclusive design for all. Some examples of high-end restaurants with zero accessible entrance are as follows (Fig 3).

Figure 3

Even the approach towards these restaurants is in accessible as it is mostly being used for parking. The assessed restaurants present numerous instances where ramps are constructed improperly, necessitating adjustments to enhance functionality. Some examples shown in figure 4.

Figure 4

Figure 5

Figure 6

Café Aylanto: (a) shows ramp and stairs present at the façade. (b) Fuchsia Kitchen: shows raised floor with

stairs but there is a ramp provided while the entrance is also wide enough

Even among the restaurants that have implemented ramps, there is a notable deficiency in the quality of construction, deviating from established standards. For example, in the butler’s chocolate café (Fig 4.) there is a ramp present on the exterior entrance however, there is also an entrance into the dining space which has stairs yet no ramp, so in this case, the ramp present at the façade comes into question as the purpose is not even being fulfilled within the functional space. Regrettably, these inadequately constructed ramps not only render the facilities inefficient but also designate them as wasted time, material and space. Instead, there is a pressing need for the installation of well-designed ramps at the entrances of every commercial building. An example is as follows:

Figure 7 (a)(b)

Tactile

All of the selected restaurants that were assessed, there is zero use of tactile flooring in there internal context (Fig 8). Tactile flooring as a crucial aspect for disabled users specially people with visual impairments for whom way finding is almost impossible without the use of it. This indicates the lack of association as well as discrimination against the disabled user making these spaces completely inaccessible for them.

Figure 8

Figure 9

Figure 9

The restaurants shown in Fig 9, Also indicates that there is no use of tactile flooring within the interior, instead many of the restaurant have dining spaces that are above the ground level making those spaces dangerous for the use of disabled people.

Signage

Some of the restaurants have implemented a thoughtful signage system to enhance user experience and aid in way finding. Well-designed signage can significantly improve navigation within a space and contribute to a positive customer experience. Entrance signage outside the building communicates the identity of the restaurant and provides directional information guiding users towards the entrance. Internal signage within the building guides users to important rooms and spaces such as toilets or emergency exits and assists in wayfinding within the restaurant. Ramp signage enhances inclusivity by providing clear information for individuals with different mobility needs. Emergency exit signage clearly indicates the location of emergency exits for safety purposes and ensures that users can quickly identify escape routes in case of an emergency. While toilet signage helps users to easily locate restroom facilities. By incorporating these elements, the restaurants are not only helping users navigate the space efficiently but also creating a safer and more inclusive environment. Some good examples of application of signage in the restaurants is as follows (Fig 10.):

Figure 10

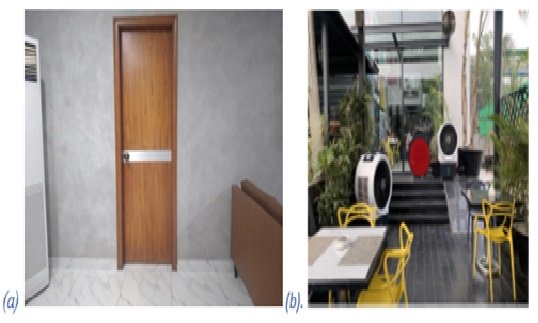

Forks and Knives: Shows signage for Emergency exit as well as Toilet (b)Patakha boti: shows signage for emergency exit(c)PF Chang’s: shows the signage for male and female toilets (d) Sichuan: shows signage for

the entrance to the restaurant

While there are good examples present in the use of signage, there are also many restaurants that lack this basic requirement as well, making wayfinding difficult for the users. And though signage is present yet unfortunately 0% of restaurants have any signage for ramps provided within their settings. Fig 11. Shows multiple examples of absence of signage which is making it difficult to identify the space for example (a) is a toilet, while (b) is the entrance to the restaurant.

Figure 11

Handrails on Entrance

In the assessment of over 80 restaurants for inclusivity, it was found that the most fundamental accessibility feature ramp was absent Fig 12 (a). Even more disconcerting is the observation that among the restaurants that have taken the positive step of installing ramps, a portion of them has failed to include handrails Fig 12(b). This oversight renders the ramps impractical and, in some cases, poses a potential safety hazard. Handrails are essential components of an inclusive infrastructure, providing crucial support and stability for individuals with varying mobility needs. The absence of either ramps or handrails in certain restaurants not only raises serious concerns about adherence to accessibility standards but also underscores the urgent need for a comprehensive reevaluation and improvement of these public spaces to ensure they are truly inclusive and accommodating for all people.

Fig 12. Shows several samples of restaurants that have not provided ramps or handrails. Without these essential accessibility features, the access of disabled persons to these spaces is compromised.

Figure 12

Circulation Space for Wheelchair

The circulation space within the restaurant is the scope of study here. After the assessment it was concluded that out of all the restaurants that were studied, only 3 had an ample space provided within the dining setting for the swift movement of the wheelchair but still could not fulfill the purpose because of different levels subjected within the space that makes the space inaccessible for disabled posing a threat to their safety and others are too congested with narrow pathways that lead to important functional spaces such as restroom which makes them inaccessible for wheelchair users as shown in (Fig 13 a ,b).

Figure 13

Figure 14

Addition to this predicament, there exists another category of restaurants that compounds the issue by entirely omitting dining facilities on the ground floor. The sole approach to these dining spaces is through staircases, and notably absent are provisions for lifts, thereby creating a complete segregation that disproportionately affects individuals with disabilities thus compromises the basic principle of universal accessibility for people with mobility challenges. (Fig 14).

Toilets

There are almost no restaurants that have dedicated accessible toilets. The absence of any designated toilets for disabled individuals within the assessed 80+ restaurants underscores a critical deficiency in the design policies of these commercial spaces. The absence of accessible restroom facilities perpetuates a form of exclusion that hinders the fundamental right of individuals with disabilities to navigate public settings comfortably.

The lavatory arrangement at Gourmet grill is a step raised above the ground level making it inapproachable for wheelchair users to navigate. There isn't enough room between the entrance and the privacy wall making it difficult to enter and circulate within the space (Fig 15a). The sink present in the restroom is not suitable for a wheelchair user as it is higher then the standard dimensions allocated while the circulation space is also very congested (Fig 15b). The space between the sink and toilet is extremely narrow so there is no possibility for wheelchair user to utilise this space (Fig 15c). the entrance to the space is too narrow as the dimensions of the door are 2’6” which is not accessible by a wheelchair.(Fig 15 d).

Figure 15

There are also some cases in which the toilets are located on the 1st floor without any circulation provided through lifts, these spaces are not serviceable for people with disabilities and the

elderly.

Despite the large sized restroom areas within the toilets there is still lack of provision of important fixtures example handrails are set with no proportionate height for use by all. (Fig 16 a,b) shows this restroom which is located on first floor that is only accessible by a narrow staircase and has a congested entrance and space.

Figure 16

Emergency Exits

The assessment of all the restaurants reveals a critical safety concern, as only two restaurants have designated emergency exits. Even more alarming is the fact that these exits, while existing, present formidable obstacles for disabled individuals. The passageways leading to these emergency exits are noticeably narrow, creating a significant impediment for those with mobility challenges. Furthermore, the emergency doors themselves are heavy and require a considerable amount of force to operate, posing a substantial difficulty for people with disabilities in the event of an evacuation. Fig. 17(a) and (b) shows the two restaurants that have provided emergency exits. The signage is provided to make wayfinding easier for all users.

Figure 17

Overview of the Study

The results of the research show that the implementation of the inclusive design principles of each restaurant is extremely low. This raises serious concerns regarding the built infrastructure of Lahore and the need for policies that can provide necessary provisions for disabled people within public settings. Out of 81 restaurants the total compliance of each of the attributes of the survey carried out is as follows:

Table 6

|

Design attributes |

Parking |

Ramps |

Tactile |

Signage |

Handrails on entrance |

Circulation space for wheelchair |

Toilets |

Emergency exit |

|

No.

of restaurants that implemented the attributes. |

1 |

13 |

0 |

13 |

0 |

3 |

1 |

1 |

Conclusion

The findings unambiguously demonstrate the dismal reality of a non-inclusive environment in Lahore restaurants. The compliance results for the inclusivity evaluation tool demonstrate a notable lack of alignment with users' different demands, notably those of people with disabilities (PWDs). None of the restaurants assessed lacked compliance with any local or international disability inclusion standards. A few restaurants have accessibility features but they are not sufficient and various other design components must be introduced or modified to make the spaces more inclusive.

Recommendations

Based on the lacking’s and findings drawn the following recommendations by ADA (Standards for Accessible Design) have been compiled in the form of graphical representations for future use in the context of inclusive design. (Fig: 10)

Parking

Parking spaces for people with disabilities must be positioned on an accessible approach to a building and as close as feasible to the accessible entrance or lift to the building or institution. Car parking spots at 90° to the walkway must be at least 3500 mm (11'-6") wide. The planned parking spot length must be at least 5000 mm (16'-6"). For vehicles that run a rear-mounted hoist, an additional 1000(3'-3") - 1300(4'-6") mm is needed. (Fig 18).

Figure 18

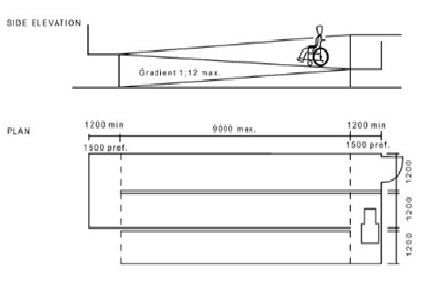

Ramps

The accessibility to a ramp must be level, with adequate visibility and wheelchair turning space. A ramp that is not a curb or step ramp has a maximum slope of 1 in 12. Transitions from one slope to another, such as at the base and top of ramps, must be marked with visible, textural, and, ideally, aural contrast. The tread width of a ramp shall be not less than 1200 mm (3’-9”) (Fig 19)

Figure 19

Handrails

Handrails at a height of 840 mm (2'-7")-900 mm (2'-9") must be installed on both sides of the ramp. Upstands or edge rails may also be used. Additionally, a safety rail must be installed to prevent the user from falling under the railing. (Fig 20).

Figure 20

Toilet Handrails with Commode and WC Heights

The

minimum size shall be 4’9” x 5’7”. The minimum clear opening for the door

should be 2'9". and the door will swing out. The toilet must have an

appropriate configuration of vertical/horizontal handrails with a clearance of

1.9" from the wall. The W.C. seat should be 1'6" above the floor. Fig

21(a), (b).

Figure 21 (a)(b)

.jpg)

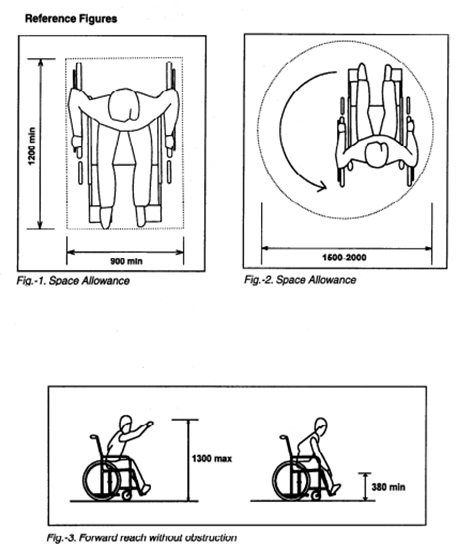

Wheelchair Space Allowance and Turning Radius

Dimensions for the space allowance shown in the

figure below are (1200mm = 4ft), (900mm = 3ft), (1600-2000mm =5 to 6ft),(1300mm = 4.2ft), (380mm = 1.2ft).Fig 22.

Figure 22

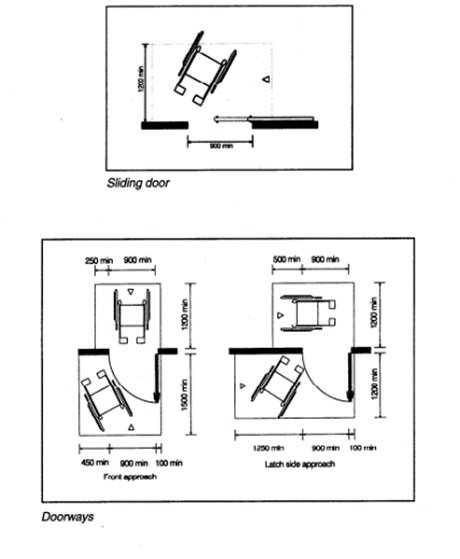

Entrance and Exit Door

Each entrance to a workplace should be accessible. Check if the dimension of the circulation pathways is suitable. It should also guarantee that circulation pathways are clear of impediments, well-marked, and sufficiently secured. (Fig 23).

Figure 23

Signages

Every aspect of signages should be present in the internal and external environment of the building for improved way finding. Signs must be in contrasting colours and preferably engraved in prominent relief so that visually impaired people may get the information they carry through touch for example, Green indicates safety or go; yellow or amber indicate risk or caution; while red indicates danger. Entrance should be clearly identified using international symbols of accessibility. (Fig 24).

Figure 24

References

- Afzal, S. (2020). Architecture a social responsibility reforming urban surroundings a barrier free responsive environment enabling limited ability: cases from karachi, pakistan. Department of Architecture & Planning, NED University of Engineering & Technology, City Campus Maulana Din Muhammad Wafai Road, Karachi., 44. https://doi.org/10.53700/jrap1922015_5

- Ahmed, M., Khan, A. B., & Nasem, F. (2011). Policies for special persons in Pakistan: Analysis of policy implementation. Berkeley Journal of Social Sciences, 1(2), 1-11.

- Americans with Disabilities Act (1990). Access Board Washington, DC.

- Boys, J. (2014). Doing disability differently: An alternative handbook on architecture, dis/ability and designing for everyday life. Routledge.

- Boys, J. (2017). Disability, space, architecture: A reader. Taylor & Francis

- Imrie, R., & Hall, P. (2003). Inclusive design: designing and developing accessible environments. Taylor & Francis.

- Preiser, W. F. (2008). Universal design: From policy to assessment research and practice. International Journal of Architectural Research, 2(2), 78-93. https://doi.org/10.26687/archnet-ijar.v2i2.234

- Reid, R. (2021). Universal Design in the Restaurant Industry: Bridging the Gap between ADA Guidelines and Customer Needs (Doctoral dissertation, University Honors College, Middle Tennessee State University).

- Syed, M. A. (2022). ‘Pakistani-people-with-disabilities’. Tribune. https://tribune.com.pk/story/2365146/pakistani-people-with-disabilities

- Afzal, S. (2020). Architecture a social responsibility reforming urban surroundings a barrier free responsive environment enabling limited ability: cases from karachi, pakistan. Department of Architecture & Planning, NED University of Engineering & Technology, City Campus Maulana Din Muhammad Wafai Road, Karachi., 44. https://doi.org/10.53700/jrap1922015_5

- Ahmed, M., Khan, A. B., & Nasem, F. (2011). Policies for special persons in Pakistan: Analysis of policy implementation. Berkeley Journal of Social Sciences, 1(2), 1-11.

- Americans with Disabilities Act (1990). Access Board Washington, DC.

- Boys, J. (2014). Doing disability differently: An alternative handbook on architecture, dis/ability and designing for everyday life. Routledge.

- Boys, J. (2017). Disability, space, architecture: A reader. Taylor & Francis

- Imrie, R., & Hall, P. (2003). Inclusive design: designing and developing accessible environments. Taylor & Francis.

- Preiser, W. F. (2008). Universal design: From policy to assessment research and practice. International Journal of Architectural Research, 2(2), 78-93. https://doi.org/10.26687/archnet-ijar.v2i2.234

- Reid, R. (2021). Universal Design in the Restaurant Industry: Bridging the Gap between ADA Guidelines and Customer Needs (Doctoral dissertation, University Honors College, Middle Tennessee State University).

- Syed, M. A. (2022). ‘Pakistani-people-with-disabilities’. Tribune. https://tribune.com.pk/story/2365146/pakistani-people-with-disabilities

Cite this article

-

APA : Sarwar, M. T., Tahir, S., & Muntaqa, A. (2023). A Disability Survey of Restaurants in Lahore. Global Sociological Review, VIII(III), 18-42. https://doi.org/10.31703/gsr.2023(VIII-III).03

-

CHICAGO : Sarwar, Muhammad Taimur, Shua Tahir, and Amina Muntaqa. 2023. "A Disability Survey of Restaurants in Lahore." Global Sociological Review, VIII (III): 18-42 doi: 10.31703/gsr.2023(VIII-III).03

-

HARVARD : SARWAR, M. T., TAHIR, S. & MUNTAQA, A. 2023. A Disability Survey of Restaurants in Lahore. Global Sociological Review, VIII, 18-42.

-

MHRA : Sarwar, Muhammad Taimur, Shua Tahir, and Amina Muntaqa. 2023. "A Disability Survey of Restaurants in Lahore." Global Sociological Review, VIII: 18-42

-

MLA : Sarwar, Muhammad Taimur, Shua Tahir, and Amina Muntaqa. "A Disability Survey of Restaurants in Lahore." Global Sociological Review, VIII.III (2023): 18-42 Print.

-

OXFORD : Sarwar, Muhammad Taimur, Tahir, Shua, and Muntaqa, Amina (2023), "A Disability Survey of Restaurants in Lahore", Global Sociological Review, VIII (III), 18-42

-

TURABIAN : Sarwar, Muhammad Taimur, Shua Tahir, and Amina Muntaqa. "A Disability Survey of Restaurants in Lahore." Global Sociological Review VIII, no. III (2023): 18-42. https://doi.org/10.31703/gsr.2023(VIII-III).03